Go to Page

St. Columbkill.

August 3rd 1839.

Dear Sir,

I now come to treat of the islands (of Aaron), the most interesting of (all) the islands I have yet visited; but I cannot spare time lo translate the documenls in connection with them or go into anything like detail. I shall confine myself to the description of the pagan and Christian remains which should be shewn on the Ordnance Map with such remarks on the age and history of each as will occur to me as I proceed. The translation and proper elucidation of the ancient Irish poems relating to the early history of these islands can only be made in Dublin, where the old Glossaries and other expositors of the old language in which they are written, are to be had. For this and other weighty reasons I shall forbear entering into the history of the different tribes Of the Firbolgs who established themselves in these islands during lhe early period of Irish history.

Situation. The three islands of Aran, which constitute one parish and half a barony are situated at the mouth of the bay of Galway about 28 Irish miles to the west of the town. They lie in a straight line in a north-west and south-east direction.

Name. Augustin Mac Raidin, Canon of the island of Saints in Lough Ree in the Shannon gives us the following derivation of the name of this is]and in his life of St. Endeus written about the year 1390:

Haec Insula dicta Arann .i. ren in Latino quia ad simili-

tudinem renis in animali se habet; qui in medio est angusta et in extremitatibus est grossa, i.e. This island is called Arann i.e. (ren) {kidney} in Latin because it has itself {i.e. it is} like a kidney in an animal, because in the middle it is narrow and in the extremities it is gross.

Acta SS. p. 706, col I, c. 9

On this passage Colgan has written the following note:

Haec insula dicta Arann .i. ren in latino, C. 9. Rectíus Ara .i. ren dicta. Nam vox Hibernica renem denotans in casu recto dicitur Ara, et in casu gignendi sive secundo Arann. Unde vulgo haec insula Ara na naomh .i. Ara Sanctorum a multitudine sanctorum, quae in ea olim tempore Sancti Endei et successorum vixerunt, appellatur. Jacet in oceano, inter extremes Conaciae et Tuamoniae fines ad provinciam Conaciae hodie et jurisdictionem spiritualem Archiepiscopi Tuamensis spectans, licet olim ad jura regum Momoniae spectasse haec vita et vita S. Albei indicent. Sunt autem tres insulae cognomines; plenae cellis, sacris sanctorum exuviis et tumulis vicinae, et oceano interluente divisae; et singulis Ara nomen est.

This island is called Arann, i.e. ren in latin. More correctly called Ara; for the Irish word signifying ren, a kidney, is in the rectus casus made Ara, and in the Genitive or second case Arann*. Hence this island is called Ara na naomh i.e. Ara of the saints, from the multitude of saints who lived

on it formerly in the time of St. Endeus and his successors. It lies in the ocean between the extreme boundaries of Connaught and Thomond, belonging at the present day to the province of Connaught and the spiritual jurisdiction of the archbishop of Tuam, although (that) it formerly belonged to the rights of the kings of Munster this life and the life of St. Albeus indicate. There are three islands of the same name {all} containing many churches, and the sacred remains and tombs of saints. They lie adjacent to each other but are separated by the ocean, which flows between them. Ara is the name of each.

Acta SS. p. 710, Col 2, note 18.

* [In left-hand margin:] See Cormac's Glossary in Voce Airther where the three Islands of Aran and their distinguishing epithets are given.

On this note Of Colgan I have to remark that I do not believe that the Middle island and South island were ever called Ara, for if so, and if the name Ara means Ren or kidney, it is not applicable whereas it is not inapplicable to the Great island, nor to the larger of the North Aran islands off the coast of Donegal. See my letter on these islands written at Dunglow. Martin in his Description of the western Islands of Scotland gives the following ridiculous derivations of the name of the Arran island belonging to that Country.

The name of this isle is by some derived from Arran {recte Arán} which in the Irish language signifies Bread; others think

it comes more probably from Arin or Arfyn, which in their language is as much as the place of the Giant Fin Mac Coul's slaughter or execution; for Aar signifies slaughter, and so they will have Arin only the contraction of Airin or Finn; the received tradition of the great giant Fin Mac Cowl's Military valour, which he exercised upon the natives here, seems to favour this conjecture; this they say is evident from the many stones set up in divers places of the isle, as Monuments upon the graves of persons of note that were killed in battle.

This derivation is as good as that given in Inishowen of Malin, viz Mala Fhinn i.e. Finn's bag!

The next derivation is that offered by Vallancey, which is not worth attention; and the latest is the arbitrary guess of John T. O'Flaherty A.B., who, in his sketch of the History and Anliquities of the islands of Aran has collected that Aran means lofly or mountainous in the Gaelic, because several mountains in Ireland, Scolland, and Wales are so-called.

As I have some years since remarked in speaking of the north Isles of Aran off the coasl of Donegal, unless Augustine Magraidin's derivation be correct, I do not know what to make of it unless indeed, that, as it is a very ancient name, it may have been called after Aaron the brother of Moses! But as the Nominative form is Ara, and the Gen: Arann or Airne and the Dat: or Oblique Arainn, I fear that to derive

it from Aaron, the brother of Moses, would now be considered visionary. The same reason knocks Martin's (two) traditional derivations completely on the head, and John O'Flaherty's must be received with great suspicion till he or some body else shews where the hills or mountains are in Ireland that bear the name Ara. Neither is it probable that the name is derived from ár - tillage or the Latin verb aro, to plough, because nothing can be produced to prove that the ancient Irish, who, according to Pynnar and other English writers, ploughed by the taile, were ever able to conslruct such ploughs as would plow fields of stone, although it must be acknowledged that it is a constant tradition in Ireland that Mo Ghob artifex, commonly known by the name of "the Gobbaun Saer", constructed a plough which plowed the fields without being dragged by the tailes of horses or by any other force, being propelled by its own mechanical construction. Unless, therefore, the monk's derivation of this name be correct, and none so ancient or so respectable has been yet produced, the meaning of this name must remain as uncertain as many of those of the same antiquity are now and will be for ever.

HISTORY

I. ARA MHOR OR THE BIG ISLAND

I shall first transcribe what the learned and acute O'Flaherly wrote on these islands in 1684, and then proceed to describe the remains on them according to the order of lheir antiquity

The three isles of Arran half Barony extending in length from East to west have the Barony of Moycullen on the north, Moyclea in Corcomroe Barony and County of Clare on the East, and the cape of Kerry head far off in sight stretched out in the sea on the south. They are fenced on the south side with very high cliffs, some three score, some four score and five score fathoms(a) deep against the western ocean's approach.

The soil is almost paved over with stones, so as in some places nothing is to be seen but large stones with wide openings between them where cattle break their legs. Scarce any other stones there but lime stones and marble fit for tombstones, chimney mantle trees and high crosses. Among these stones is very sweet pasture so that beef and mutton are better and earlier in season here than elsewhere; and of late there is plenty of cheese & tillage.

[NOTES BY JOHN O'DONOVAN]

(a) The height of the cliff at Dun Aengus is 302 feet.

Mucking ({.i. manuring}) and corn is the same with the seaside tract. On the shore grows samphire(b) in plenty, ringroot or seaholly(c) and sea cabbage. Here are Cornish Choughs with red legs and bills. Here are ayries (i.e. nests) of hawks and birds which never fly save over the sea, and therefore are used to be eaten on fasting days, to catch which people go down with ropes tied about them into the caves of cliffs in the night,(d) and with a candle light kill abundance of them. Here are several wells and pools, yet in extraordinary dry weather people must turn their cattle out of the islands, and the corn fails.

They have no fuel but cow dung(e) dried with the sun, unless they bring turf in from the western continent.

[NOTES BY JOHN O'DONOVAN]

(b) The (present) inhabitants of Aran send Samphire to Dublin, JO'D.

- Half-way down

Hangs one that gathers Samphire: dreadful trade!

Methinks he seems no bigger than his head.[Shakespeare, King Lear]

(c) Cuilleann tragha in Irish. It is used as a medicine by the islanders.

(d) See a similar account of the manner in which the inhabitants of the islands of St. Kilda go down the cliffs to catch birds and get eggs, in Martin's account of that Island, p. 105.

They have cloghans,(f) a kind of buildings of stones (laid one upon another) which are brought to a roof without any manner (.i. kind) of mortar to cement them; some of which cabins will hold forty men on their floor; so ancient that nobody knows how long ago any of them were (was) made. Scarcity of wood and stone of fit stones [sic] without peradventure (.i. procul dubio) found out the first invention.

There is a west island on the South (recté north) west called Ilan na (da) branoge,(g) where they go to slaughter seals yearly, and where there is abundance of Samphire.

From the Isles of Aran and the west Continent often appears visible that inchanted island called O'Brassil, and in Irish Beg Ara(h) or the lesser Aran, set down in carts (.i. charts) of navigation, whether it be real

[NOTES BY JOHN O'DONOVAN]

(e) [Referred to on MS p. 179] You could see stacks of dried Cow-dung (bóithreám) (thatched) on the Middle island. They now however generally carry turf from the north shore.

(f) For a description of one of these Cloghauns See p. ? See also letter on High Island belonging to the parish of Omey, and the one about Inish-Gluairé off the coast of Erris in Mayo.

(g) Now always called Oileán dá Bhranóg in Irish and Brannock or Brannoge island in English. It lies off the T.L. of Onaght at the west extremity of the Great Island.

(h) They tell stories about this island still. See Mayo Extracts for more stories about it. The Aranites now call it New Aran.

and firm land kept hidden by the special ordinance of God or the terrestrial Paradise or else some illusion of airy clouds appearing on the surface of the sea, or the craft of evil spirits is more than our judgments can sound out. There is westward of Arran in sight of the next continent of Ballynahinshy barony Skerd(i) a wild island of huge rocks, the receptacle of a deal of seals thereon yearly slaughtered. These rocks sometimes appear to be a great city far off, full of houses, castles, towns, chimneys, sometimes full of blasing flames, smoke and people running to and fro; another day you would see nothing but a number of ships with their sails and riggings; then so many great stakes (stacks) or reeks (ricks) of corn and turf, and this not only on fair sun-shining days, whereby it might be thought the reflections of the Sunbeams or the vapours arising about it, had been the cause, but also on dark and cloudy days happening. There is another like

[NOTES BY JOHN O'DONOVAN]

(i) Now the Skerd rocks lying in the ocean due west of Casheen Bay and about 9 miles N.W. of the western extremity of Aranmore. Those optical delusions are not much talked of now, because the romance of former days is fast disappearing.

number of Rocks called Carrigmeacan(j) on the same Coast, whereon the like apparitions are seen. But the enchanted island of O'Brazil is not always visible as those Rocks, nor those Rocks have always those apparitions.

There is now living Murrough O'Ley,(k) who imagines he was himself personally in O'Brazil for two days, and saw out of it the Isles of Arran, Golamhead, Iross beg hill, and other places of the western continent he was acquainted with. The manner of it he relates that being in Irros-Ainhagh in the South side of the Barony of Ballynahinshy, about nine leagues from Galway by sea, in the month of April Anno Domini 1668, going alone from

[NOTES BY JOHN O'DONOVAN]

(j) Now Carrickmackan near the mouth of Casheen Bay and (nearly) due north of the Brannock isles off the western extremity of Aranmore.

(k) This story is still told. Some few generations ago the crew of a (fishing) boat passing an island (which) they did not know, landed thereon to refresh themselves. They had no sooner landed than a man appeared and told them they had no business there as the island was enchanted. They therefore immediately returned to their boat, but as they were going away the islander gave one of them a book with directions not to look into it for seven years. He complied with this request, and when he opened and read the book he was able to practise surgery and physic with great success. This man's name was Lee, and the book got from the enchanted man in O'Brazil or New Aran remained as an heir- Continued on page 183.

one village to another in a melancholy humour upon some discontent of his wife, he was encountered by two or three strangers, and forcibly carried by boat into O'Brazil as such as were within it told him, and they could speak both English and Irish; he was ferried out hoodwinked in a boat as he imagines till he was left on the sea side by Galway, where he lay in a friend's house for some days after being very desperately ill, and knows not how he came to Galway there. But by that means(l), about seven or eight years after he began to practice both Chirurgery and physic, and so continues ever since to practice, tho' he never studied or either all his lifetime before, as we all, that know him since he was a boy, can aver.

[NOTES BY JOHN O'DONOVAN]

Resumed from page 182. loom with (in) his descendants until some 20 months since, when it was purchased by a bookseller in Dublin. It is believed that it is written in Irish or Latin.

(l) Here O'Flaherty's version of the story is lame and defective, for "by that means" affords no explanation of the manner in which the quack obtained his Medical information, but the introduction of the Medical book makes the story perfect. The truth seems to have been this, that Lee, who got this book from some of his relatives who were hereditary physicians, and taking it in head to turn quack forged.

In the western ocean five or six leagues from the continent there is a sandbank about 30 fathoms deep in the sea, and by a very small breadth, which extends from Ulster to Munster, all along the western coasts of Connaught: It is called in Irish Imaire-boy,(m) or the yellow ridge, and in English the Codfishing bank, where people in the summer season used to go in boats a-fishing from Bofin, the Owles (.i. Umallia), Irros-Downan, and some parts of the barony of Ballynahinshy, and are there in their boats over night. From this bank about 20 years ago, a boat out of the Owles was blown southward by night, next day about noon they spyed land so near them that they could see sheep within it, and yet durst not for fear of illusions touch shore, imagining it was O'Brazil, and they were two days coming back towards home. So much of the inchanted island; whence we come back again to Arran.

The islands of Arran are famous for the numerous multitude of saints there living of old and interred on them trained in religious austerity and propagating monastic discipline in other parts; venerable for many sacred churches, chappells, wells, crosses, sepulchres and other holy reliques of Saints still there extant as monuments of their piety, reverenced

[NOTES BY JOHN O'DONOVAN]

(m) I suppose this cannot be shewn on the Ordnance Map.

for many rare privileges of sacred places therein, and the instant divine punishments inflicted on such as dare violate or prophane; frequently visited by Christians in pilgrimage for devotion, acts of penance and miraculous virtues there wrought.

Ara mhor,(n) the greatest and furthest west of these, contains 24 quarters of land and is 24 miles in compass, wherein on the south side stands Dun Engus,(o) a large fortified place on the brim of a high cliff a hundred fathoms deep; being a great wall of bare stones without any mortar, in compass as big as a large Castle-bawn with several long stones on the outside erected slopewise against any assaults. It is named of Engus Mac Uathmore of the reliques of the Bolgmen in Ireland there living about the birth time of Christ. On the east side thereof the island is so low that about the year 1640 upon an extraordinary inundation, the sea overflowing that bank went across over the island to the north-west.(p)

[NOTES BY JOHN O'DONOVAN]

(n) Colgan is entirely wrong in his description of this island, see p. [?]

(o) For a description of Dun-Engus see page [?]

(p) This (inundation) is still traditionally remembered.

The king's Castle and Manner (manor) of Arkin(q) stood on the north side over the ship harbour; for the service of which Castle all the patents in capite of West Connaught granted by Queen Elizabeth and King James were held, in place whereof now stands a citadel, in the Usurper Cromwell's time erected.

This island was inhabited by Infidells ({.i. Pagans}) out of Corcomro, {the next adjacent country in the County of Clare} when St. Enna got it by donation of Engus king of Munster, anno Christi circiter 480 {Ware Antiq: p. 249} who then laid the first foundation of piety and sowed that small grain of mustard seed, which so encreased that this Island was called Ara Sanctorum {Math. 13, 31} whereunto may be applied the prophecy of Isaias. In cubilibus, in quibus priûs dracones habitabant, orietur viror Calami et junci. Et erit ibi semita et via, et via sacra vocabitur. Isaiae 35, 7.

The author of St. Kieran, {first abbot of Cluain-mac nois, anno 549 deceased,} his life thus expresses the infinite number of Saints in that island in his own time. In quâ multitudo Sanctorum

[NOTES BY JOHN O'DONOVAN]

(q) See an account of this on page [?] In an inquisition taken in the reign of James I, the half Barony of Aran is called after this Castle. "The half Barony of Arkyn containing the Isles of Arren consisting of 36 quarters", &c.

Virorum manet et innumerabiles Sancti omnibus incogniti nisi soli Deo omnipotenti, ibi jacent. The like expression is to be found in Albeus, Bishop of Imly, his life, thus: Magna est illa insula et est terra Sanctorhun qui nemo scit numerum Sanctorum qui sepulti sunt ibi nisi solos Deus.

St. Enna, son of Conall Dearg of the noble Orgiellian family in Ulster, and brother in law by his sister to King Engus of Munster aforesaid, followed the evangelical precept of forsaking a rich patrimony for Christ and his merits; brought him to be abbot beyond seas in Italy before he came with 150 religious persons to Aran, where he lived to his decrepid age upwards of 58 years: For St. Kieran aforesaid lived 9 years under his discipline and left Anno 538 {Ussher in Indice Chronolog:}. His successor abbots of Arran continued, as I suppose, to the time of ({the}) suppression of abbeys, the last of whom I find recorded was Donatus O'Leyn, abbot of Arran Anno Di. 1400.

The memory of St. Gregory the Great kept in this island was doubtless become much reverend of old in Ireland and honoured with the title of Golden Mouth as Cumianus writes in his letter anno circiter 634 {Ussher loco cit: et in Sylloge Epist: p. 31}. Ad Gregorii, Papae Urbis Romae Episcopi a nobis in commune

suscepti et oris aurei appellatione donati verba me converti, by which name he is known to this day in Irish.

Giraldus Cambrensis {Topograph: Hib: dist 2: Cap: 6.} was misinformed to say that St. Brendan was chief patron of this island, {St. Brendan visited St. Enna here once passing to Kerry, and another time on his second adventure of navigation on the ocean} and that human carcasses need no burial in it, as free from putrefaction, which last was attributed to Innis-Gluaire on the sea of Irros-Downan, and (.i. but) there itself it is by experience found false. But what he alleges that it did not breed rats, and that those by chance thither transported they immediately died, I believe was true in his time, for that is the nature of all the rest of the territory except the districts of Galway town. It was held an ominous presage of the following alteration that rats frequented Moycullen for one year ending in Lent 165½, at which time they all parted in one night after devouring a carcass of mutton to the bones. About the same time they infested the Castle of Bunowan for two years till it was all burnt 31st January 1652/3. In Irish they are called French mice (lucha Francacha), for there was a time when they were no-where in Ireland.

Near the Castle of Arkin was St. Enna's church and an abbey of St. Francis, both demolished for building the Citadel with their stones. So all devouring time!

Diruit, aedificat, mutat quadrata rotundis.

Not far from thence to the east remains a small chappell of St. Enna, where Sir Morogh O'Flaherty of Bonowan was buried Anno Domini 1666. {On} the outside of this chappell N.E. is the church-yard where anciently were 120 graves of saints, in one of which St. Enna was buried; where the stone laid over him is yet to be seen, together with divers other tomb stones still extant. Here numerous saints interred {as in other parts of the island} rest in peace till the day of "{the}" general Resurrection. There is on the east side of this island Port Doibhche i.e. Portus Dolii, mentioned in St. Enna's life {Cap. 16} now corruptly Port eiche; and in each of the other two other islands is Tracht-na-neach or Tracht each i.e. the horses shore, situated as ({described}) in his life {Cap. 15}. But Leamhchoill ({Cap. 14} where he is said to have first arrived in the (north side of the) island should be Ochoill, for) [it] is in the west Continent whence is a ferry (port) into the island, and Ochoill (recte Eochoill) in the island on the north side whereof hath a port for boats to arrive named from Ochoill, and another called Port Caradoc from St. Caradoc (.i. Cobharubhach) garbh to whom Killnanamanach [sic] church on the island is dedicated. Near

this port is the pool of Lough-na-ceanainne, whereof mention is made in St. Enna's life {C. 19, Col 2}. There is but a straight (.i. narrow) ship road between St. Gregory's Sound on the east of this island and Tracht each, or the horses's shore on the middle island.

But before I go farther I reflect upon an old saying I often heard, thus: Athenry was, Galway is, Arran will be the best of the three, which may be interpreted that Athenry was the creation of a Baron, and afterward the creation of Víscount of Galway was conferred on Rickard, Earl of Clanrickard, extinct with (.i. in) his son, the late Lord Marquiss, and now Arran hath the creation of an Earl.

I shall presently insert an abstract of Augusline Mac Raidin's Life of the nobly born St. Eany.

ARAN MORE, DESCRIPTION OF, ANTIQUtTIES, PAGAN

Colgan is entirely wrong in making the eastern island of Aran the largest and most remarkable, for the east island is by far the smallest of the three. This mistake is in all probabilily attribulable to some bad map. Let the the readers of Colgan reverse the map of those islands, which he must have done himself by some mistake, and then all is inlelligible, for his east Island agrees with the one which is now the most westerly. Perhaps the same force, which originally separated them from Munster, caused them to reverse their order since Colgan's time! But no; we have the authority Of Roderic O'Flaherty, who was 18 years of age when Colgan wrote, to prove that the islands of Aran were then in the same position in which they are now.

Prima autem et praecipua priscis scriptoribus Ara Oirthir .i. Ara orientalis appellatur; quia Continenti versus orientem propinquior; et vulgo Ara na naomh, id est Ara Sanctorum quia in eâ Sanctus Endeus decem construxit Coenobia, &c.

Acta SS. p. 714, Col. 2.

On this passage O'Flaherty observes: "Neither is the most Eastern the chiefest of the three Isles as he {Colganus} took it {21 March p. 714, c. 7} but rather the smallest".

To this may be added that there is no church of St. Enna's on the most eastern island.

It is an old written Irish tradition that Loch Lurgan, {which is still the Irish name of the Bay of Galway} was one of the three lakes found in Ireland by Partholan on his arrival from Greece 300 years after the flood. The oldest written authority hitherto discovered for this tradition is the poem beginning Adhamh, atair sruth ar sluagh, Adam, father, senior (progenitor) of our hosts, which some ascribe to Aengus Ceile De, the festilogist, and others to Aengus Roe O'Daly, who flourished about the year 1350

A n-erinn ar a g-cinn

Acht tri locha inradh gann

Ar deich srotha sean-abhann

Sloinnifed-sa go fír iad sin

Anmanna na d-tri sean loch sin:

Finn-loch irruis ucht glain,

Loch Lurgan, Loch Foirdreamhain

Laoi, Buas, (Banna) Bearbha buan,

Saimér, Sligheach, Modhorn, Muadh,

Fionn, Life a laighnibh go gleith

Is iad sin na sean-aibhne.

In Erin on their arrival

But three lakes of obscure fame

And ten streams of old rivers

I will name these truly

The names of these three old lakes

Finn-loch of Erris of bright bosom

Loch Lurgan {and} Loch-Foirdreaman

The Lee, the Bush, the Bann, the ever-flowing Barrow,

The Saweer {Erne hodie}, the Sligo, the Mourne & the Moy,

The Finn, the Liffey brightly flowing in Leinster

These are the seven ancient Rivers.

On these three lakes Roderic O'Flaherty has written as follows, in his Ogygia, p. 164.

Fordreman lacus est in Kierrigiâ juxta Traleiam, at Montem Mis. Finloch In Kearâ agri Mayonensis baroniâ quae olim ad Irras-Damnoniam spectasse videtur, jacet. Pro Loch Lurgan alterius Antiquarii poema habet Loch-lumny in Desmoniâ; sed iste lacus longo post tempore legitur prorupisse {Codex Lecan fol. 284} Loch Lurgan vero est sinus Maris spaciosus inter Tuamoniam et Westconactiam Galviae ad ostium, et ultra in ortum late porrectus; qui quondam fortasse firmâ terrâ a salo discretus, donec Occidentalis Oceanus confinia absorbens totum sui juris fecerit: claustrorum reliquiae videntur esse Arannae tres insulae, quae obrutu non faciles in medio profundo eminent, et editissimas praeruptas Crepidines decumanis fluctibus objiciunt; Superstes etiam in marino sinu lacus nomen a quibusdam longa traditione etiamnum Loch-lurgan, appellato.

Correct translation (Healy's is very bad)

Fordreman is a lough in Kerry near Tralee or (near) the Mountain Mis.(a)(a) Finloch (lies) in Carra, a barony in the County of Mayo, which appears to have formerly belonged to lrras-Damnon.

[NOTES BY JOHN O'DONOVAN]

(a) i.e. Near Slieve Mish in the County of Kerry. Healy's translation runs as follows: Fordreman is a lough in Kerry near Tralee, or near the mountain of Mis-finloch, in Keara in the barony(!!) of Mayo!! Oh shade of Tytler!

Instead of Loch Lurgan, the poem of another antiquarian has Loch-lumny in Desmond; but we read that this lake burst forth a long time after this period. But Loch-lurgan is a spacious bay (.i. arm) of the sea between Thomond and West (or Iar) Connaught, (extending far and wide to) the mouth of the {river} Galway (Gaillimh(b) and beyond it to the east. This was probably in ancient times separated from the sea by firm land, until the western ocean destroying the confines united the entire with itself; the remains of the barriers seem to be the three islands of Arann, which not being easily overwhelmed, stand towering in the midst of the deep, and oppose(c) their lofty & rugged cliffs to the fury of the surges.* The name of the lake is moreover preserved in that of the Bay, which is to this day, through a long tradition, by some called Loch-Lurgan.(d)

*This idea is thus expressed in English by O'Flaherty himself: "They are fenced on the South side with very high cliffs against the western ocean's approach".

[NOTES BY JOHN O'DONOVAN]

(b) That is, the Bay of Galway extends from the Islands of Aran as far (eastwards) as the mouth of the River Galway and ultra i.e. farther to the east; for it extends four miles farther, that is, as far to the east as Oranmore. Healy renders this passage in the following ridiculous manner: "Lough Lurgan though(!!) it is a spacious inlet of the sea between Thomond and West Connaught at the mouth of Galway; and extending a great distance to the east"!

(c) Healy renders this "and shew (objiciunt) their towering and craggy Summits (crepidines) by the reverberation of the surges"! Crepido does not mean summit but a cliff against which the sea beats:

Maris atrocitas objectu crepidinis frangitur.

(d) Healy translates this, "There is yet a lough, in an inlet of the sea, called also Loch Lurgan time immemorial". He must have been drunk!

This conjecture of O'Flaherty rests entirely upon the meaning of the word Loch, but as that word is found applied to arms of the sea in every part of Ireland, as Lough Swilly, Mulroy lough, Loch Garmann - no argument should be built upon it. It is possible that the islands of Arann were - at a very remote period - connected with COnnaught and Munster, but the name Loch Lurgan being applied to the Bay is no proof that this connection existed within the historical period, and the adaptation of (some of) the Cyclopean forts to the form of the Cliffs proves that the isles of Aran were (nearly) as lhey are now, at least two thousand years ago.

The early historical notices of the South Arann isles will be found in the Book of Lecan fol 277. and in Duald Mac Firbis's account of the Firbolgs. The summary of what is contained in these account(s] is briefly this, That as many of the Firbolgs as escaped from the battle of Moy-Turey ({fought Anno Mundi 2737}) fled to the islands of Aran, Ilea, Ragharee, and to the Hebrides and other islands of Scotland; that some fled to the isle of Mann and others to Britain, from which a colony of their descendants returned about the first Century of the Christian era (under the name of Clann Huamoir) and settled first in the plain of Meath under the King of Tara, where they did not remain long being unwilling to pay the exorbitant rents imposed upon them by the monarch; that they emigrated thence with their cattle and (other) possessions to Connaught where they sought the protection of Olioll

and Meave, who being relatives and friends of their race, received them with great kindness and gave them lands in Arann and along the sea in the west and south of Connaught, where they fortified themselves and gave the names of their chiefs to the lands they possessed and the forlresses they erected.

The places (situated in the west of Connaught) mentioned in these accounts as receiving their names from the Firbolgs are the following

- Dun-Aengusa in the Great Arann.

- Dun Conchobhair on Inishmaan.

- Loch Cime, now Lough Hackett near Headford.

- Rinn Tamhuin in Meadhraigh, now Tamhun point and village in Maaree parish.

- Loch Cutra now Lough Cooter near Gort.

- Rinn Beara, now Rinnbarrow point running into Lough Dergart in the Shannon in the south of the Counly of Galway.

- Muirbheach Mil, now Murbhach near Oranmore.

- Rinn Mhil, now Rinvile near Oranmore.

- Rinn Mhil now Rinvile near the Killery harbour.

PAGAN ANTIQUITIES ON ARANMORE

MILITARY

The first pagan monument in point of strength, extent and importance, on the Great island of Aran is called Dun Aengus, a name now forgotten by all the inhabitants except one old man of the name Wiggins dwelling at Killeany. He, though not of the primitive Irish race but of a colony planted here by Cromwell, remembers that the old people were accustomed to call it Dun-Innees, which is the true Irish pronunciation according to the Connaught accent. All the other inhabitants style it Dun mor, and in English the Big Fort. The tradition that formerly exisled on Aran in connection with this fortress is now totally forgotten, but it was committed to writing by Roderic O'Flaherly in his Ogygia and (in his) MS. account of Ier-Connaught written for Sir W Petty in the year 1684. He thus speaks of it in his Ogygia p. 175.

De Clanna Huamoriis Aeneas et Conquovarus Paulo ante Salvatoris adventum sub Mauda Connactiae regina floruerunt, ab hoc Dun-Aengus ingens opus lapideum sine coemento tamen, quod decentas vaccas in areâ contineret supra altissimam maris crepidinem è vastae molis rupibus erectum adhuc extat in Arannâ Magnâ sinûs Galviensis insulâ, S. Endei incolatu, et Sanctorum multitudine postea

celebri: ab illo perpetua incolarum traditione Conquovari filii Huamorii Dunum nuncupatur alia similis maceries inde non procul ad ortum in Arannâ media insula.

Correct translation. Healy's is horrible!

Of the Clanna Huamor Aengus and Conquovar flourished a short time before the birth of Christ under Meave, Queen of Connaught. From the former (hoc) (.i. Aengus {is called}) Dun Aengus, a great stonework but without cement, (still extant) which would contain two hundred cows in its area, and which is built of stones of a vast size ("erected with cliffs of a stupendous magnitude"! Healy) over a very lofty cliff of the sea in the Great Aran, an island in the bay of Galway, celebrated for the residence of St. Enda and afterwards for a multitude of Saints; from the latter (illo),(a) according to the perpetual tradition of the natives, is named the Dun of Conquovar, another similar work (maceries)(b) situated on the middle island of Aran, not far from thence to the east.

[NOTES BY JOHN O'DONOVAN]

(a) Hely was so ignorant of the construction of the Latin language that he did not know that hic was used to signify the former and ille the latter. He certainly had not common sense, or he was drunk while translating the Ogygia.

(b) Healy translates maceries in this sentence, a mound, and mistakes the construction altogether. This Hely was a Minister and A.B. of Trinity College. What a credit he was to Ireland, to Trinity College and to the church!!

And thus in his MS. account of Iar Connaught:

Ara mhor, the greatest and farthest west of these, contains 24 quarters of land and is 24 miles in Compass, wherein, on the south side stands Dun Engus, a large fortified place on the brim of a high cliff, a hundred(a)(a) fathoms deep, being a great wall of bare stones(b) without any mortar, in compass as big as a large Castle-Bawn(c) with several long stones on the outside, erected slopewise against any assaults. It is named of (i.e. from) Engus Mac Uathmore of the reliques of the Bolgmen in Ireland, there living about the birth-time of Christ; on the East side thereof the island is so low that about the year 1640, upon an extraordinary inundation the sea overflowing that bank went across over the island to the north-west.

[NOTES BY JOHN O'DONOVAN]

(a) It is only 302 feet high above the level of the sea at high water.

(b) Here we have O'Flaherty's English for the Latin maceries (and other words), but his English description is much better though the language is not so dignified as the Latin.

(c) This description is too indistinct to convey a correct idea of the extent or characteristics of Dunengus. A description is worth nothing unless it can be perfect.

For this tradition O'Flaherty might have referred lo the authority of the Book of Lecan, fol 277 p. b. c. l, where it is distinctly stated that Dun Aengusa in Ara {Dún Aengusa a n-Áraind} is named after Aengus the son of Umor, who was the leader and king of the whole Colony. It is no wonder then that his Dun should be the most remarkable of all the Bolgic forts in Ireland.

DUN AENGUSA

SITUATION AND MODERN STATE OF, DESCRIBED

John T. O'Flaherty in his ridiculous account of the islands of Aran, published in the Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy in the year 1824, attempts a description of Dun Aengus from the data furnished in the Ogygia aided by his own imagination. In page 9 he says:

It further appears from our Annals that two chiefs, Aengus and Concovar of the Huamor Sept, possessed the Isles of Aran, in the time of Maud Queen of Connaught, whose reign was not long anterior to the Christian era. Of these chiefs there are still unequivocal memorials; one in the Great Isle of Aran called Dun-Aenguis, the fortification

of Angus; the other in the Middle Island (isle), traditionally called Dun-Concovair, the fortification of Concovar. These extraordinary remains of ancient military architecture shall be described hereafter.

From these words one would be inclined to believe that John T. O'Flaherty had actually seen Dun Aengus, and to anticipate a minute description of that great fortress; but when you come to read his description of it you find him like the mountain in labour.

Parturiunt montes nascetur ridiculus mus!

Dun-Aengus, the very ancient fortification already mentioned, stands on a great precipice hanging over the sea. It is extremely rude, being composed of large stones, roughly heaped on without cement of any kind. Within its area it may contain about 200 cattle. There is another dun much of a similar description. I have already given the history of both, so far as their extreme antiquity admitted; remnants more ancient in point of military architecture, are certainly not to be found throughout the British Isles, nor perhaps throughout Europe. The other duns (seen) here are of no note.

p. 59.

Here he merely repeats the words of lhe Ogygia, and adds a remark about which he knew nothing; for it appears from the works of modern Antiquarians that there are several remnants of Cyclopean fortresses on hills in Greece which were erected before (refined) civilization began in that early civilized Country, in which, long before the period of Queen Meave or the birth of Christ the three grand orders of architecture were in use.

- First unadorned

And nobly plain, the manly Doric rose;

The Ionic next, with decent matron grace,

Her airy pillar heav'd; luxuriant last

The rich Corinthian waved her wanton wreath

The whole so measured true, so lessened off,

By fine proportion that the marble pile

Formed to resist the still or stormy waste

Of rolling ages, light as fabrics looked,

Which from the magic wand aerial rise.

These were the wonders which illumined Greece

From end to end. -

[Capt. Edward Thomson, Liberty (1736)]

These styles were unquestionably used in Greece many centuries before the birth of Christ, and from this fact another very curious one can be drawn, (i.e.) that the Tuatha De Danann and Firbolg Colonies, who (according to lhe Irish histories) came hither from Greece

must have arrived before these orders were introduced into or invented in Greece. All the remains which written tradition ascribe to them are in the Cyclopean, and therefore they must have left Greece before the refined style of architecture prevailed there. And this in my mind should go very far towards fixing the periods at which those Colonies arrived in Ireland, for if the Doric or Corinthian pillars were used in Greece at the periods these Colonies migrated from it, they cerlainly would have attempted something similar to them in the Country in which they settled. But nothing of the kind is found in Ireland. These colonies must therefore have set out from Greece before refined civilization began there; for we cannot for a moment suppose that they could have lost every trace of their refined architecture (here); the utmosl lhat could be granted is that the style would in the course of some centuries become rude in a sequestered country.

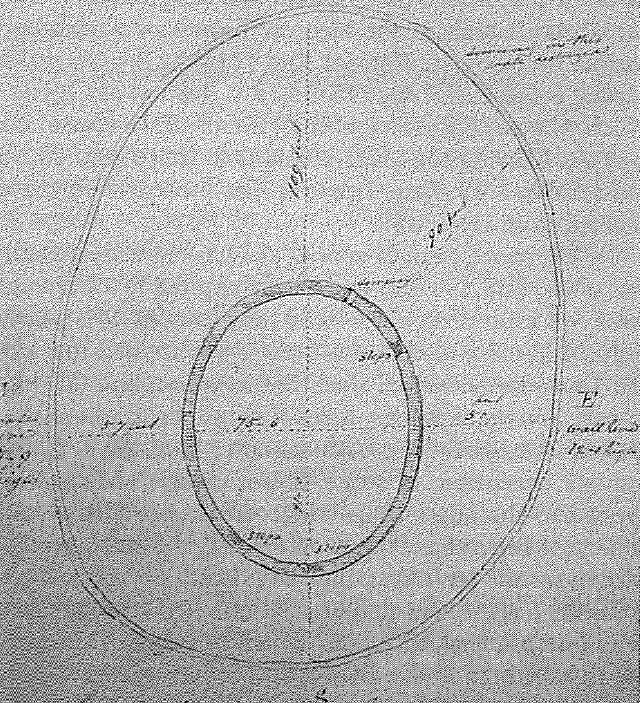

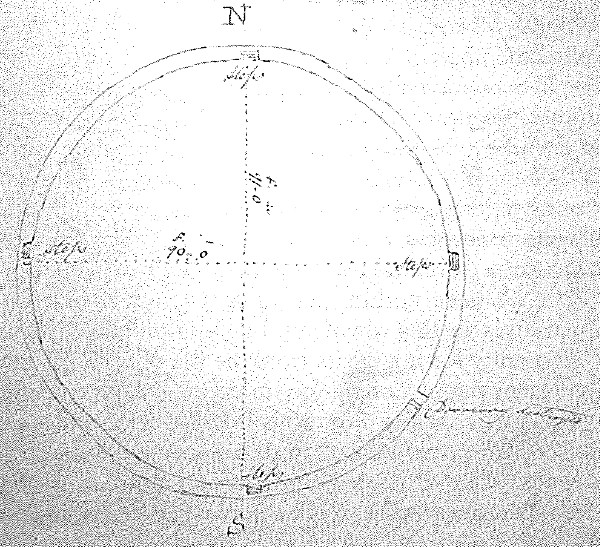

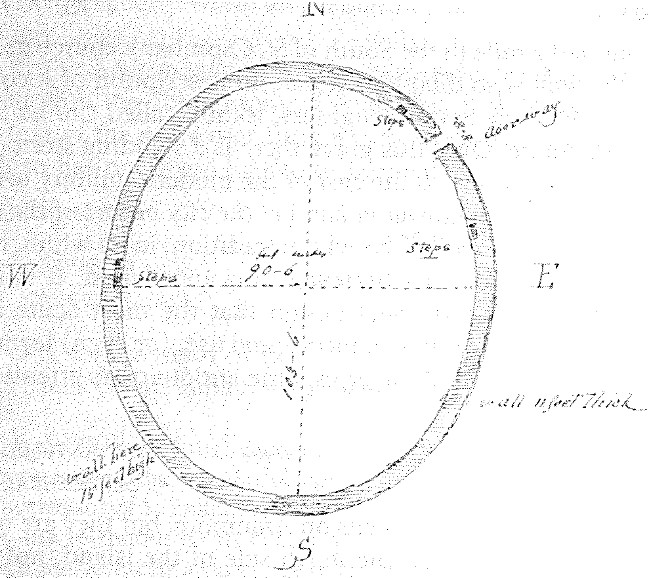

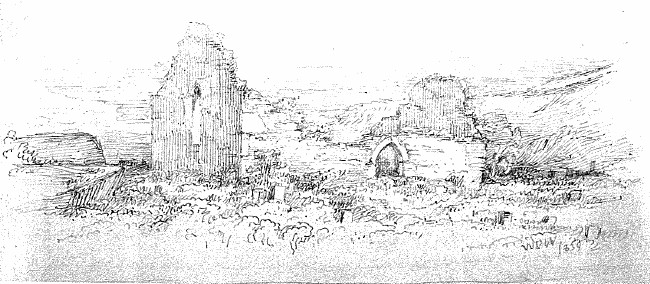

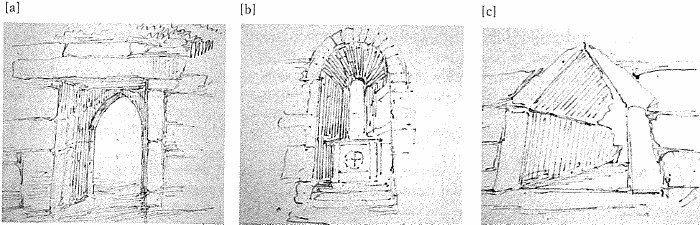

Dun Aengusa {pronounced Doon Innees} is situated on the South side of the Great Island of Aran in the S.W. of the townland of Kilmurvy on the edge of a cliff which is 302 feet above the level of the sea. It is perhaps one of the finest specimens of barbaric fortresses in the world, but very much ruined. One third of the circle of its internal keep (seems to) have been destroyed by the falling in of the cliff, and the boys of the island are destroying the remaining part in rooting for rabbits which burrow in its walls. As it stands at present, it consists of three concentric walls, of which the central one is in a tolerable state of preservation, but the two outer ones are nearly destroyed excepting in spots here and there where their original thickness and style of masonry, and in some few instances, perhaps, their height remain. The central fort or keep is by far the most perfect and interesting part. It was originally of an oval form, but now only the two thirds of the oval remain, the Atlantic having, in the course of two thousand years, worn away the remaining part. It measures from north to south, i.e. from the northern point of the ring to the edge of the cliff 150 feet, and from west to east along the edge of the cliff 140 feet. When the oval was perfect it measured 225 in length from north to South, and that it was once a perfect oval will appear clear by a comparison of it with Dun-Conchobhair on the middle island, which measures 227 feet in length from North to South, and 115 feet from west to east. The wall of this keep of Dun-Aengus

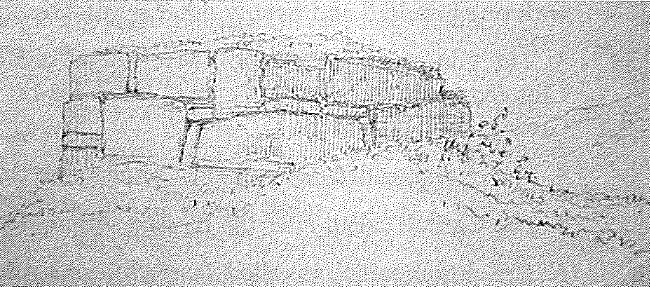

is built of large and small stones, the large ones (being placed in the) face of it, and the small ones in the centre. This wall is made up of three distinct walls built up against each other, each well faced with stones of considerable size, so that if the external one were destroyed the central one would stand independently of it, and if the central division were destroyed, the interior division would stand without it. This shews how difficult it would have been (to demolish this fortress) at the remote (engineless) period when it was inhabited.

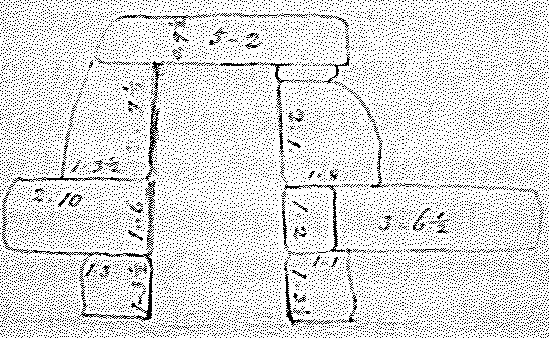

The grealest height of this wall at present is 18 feet. This is at the west side, where the original characteristics of the masonry appear. The internal division of the wall is here 3ft. 4 in. thick, the second or central division is 5ft. 0in. thick and the external division is 4ft. 5in. thick. Total thickness 12ft. 9in.

The two external divisions are here raised to the height of 18 feet, but the internal division is (at present) only 7 feet high; but it is probable that it was originally many feet higher though I think never so high as the two external parts as I find in all the other forts that the internal division is generally 4 feet lower than the other two, which are always carried to the same height.

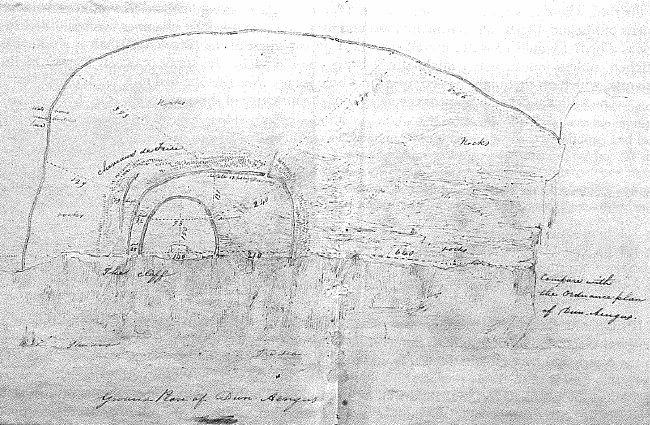

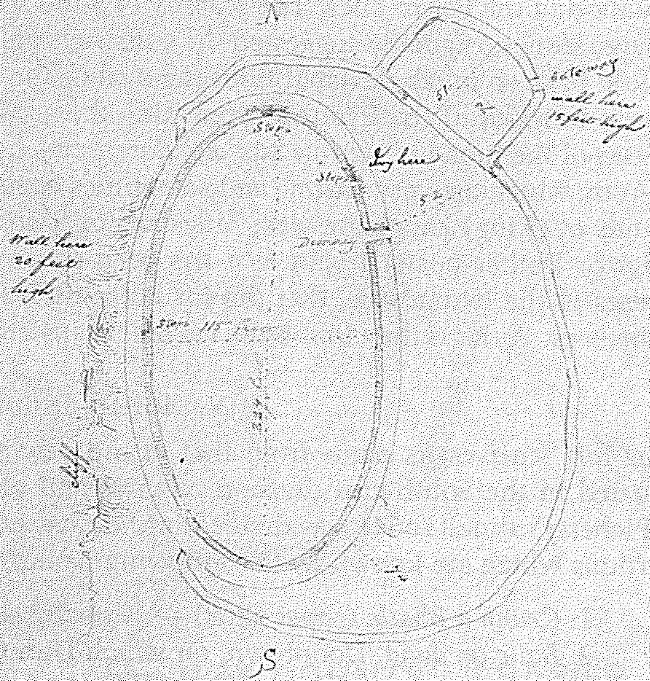

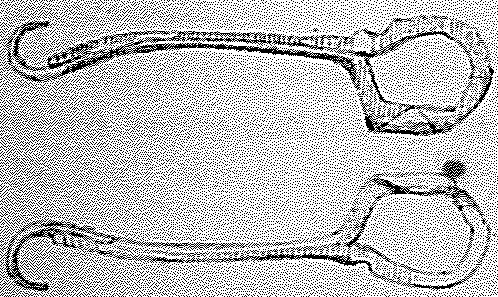

The annexed ground plan will give an idea of the extent of the outer walls of this fortress, and of ils position over the cliff. [Added in pencil: It is faithfully set to a scale.]

[The above drawing of the 'Ground-Plan of Dun Aengus' continues into MS page 207.]

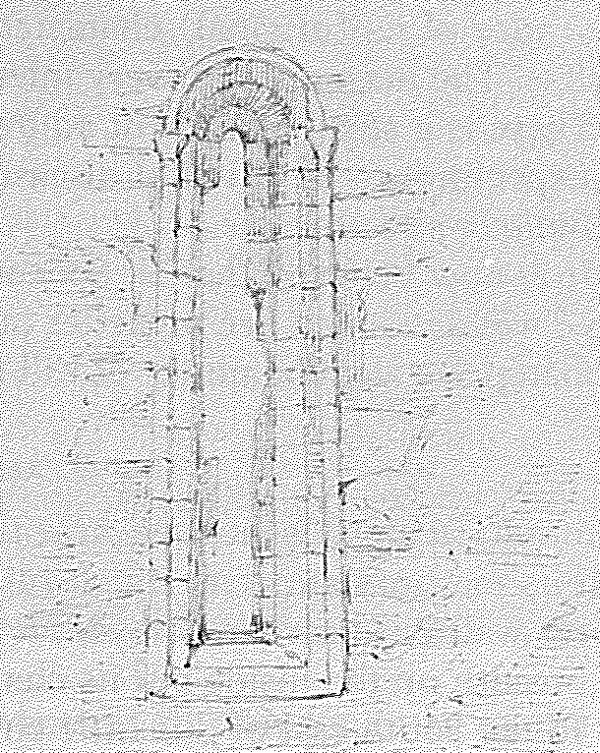

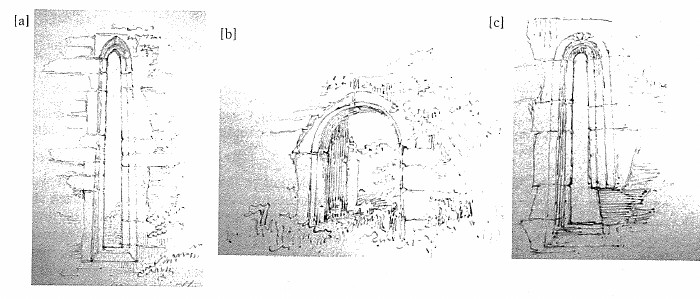

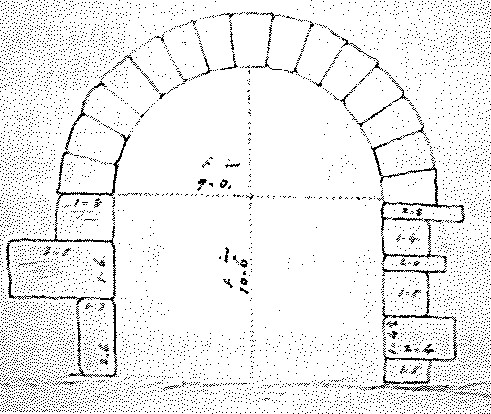

The doorway which led into this Keep is still nearly perfect. It is placed in the North east side facing the Aran Light House, which is situated on the highest point of the Island. It is nearly stopped up (on the inside) with stones which fell from the top of the wall, but I removed them on the outside down to the solid rock on which the wall is built and found the doorway to measure in height exactly 5 feet. It surprised me very much to find that this doorway does not slope like those of the Cyclopean forts in Greece (as described by Dodwell), or even like the Semicyclopean doorways of the primitive Irish churches. It is really not so gigantic or Cyclopic as the doorway of St. Mac Duagh's church at Kilmurvy. It is 3f. 4inch. in breadth at the top and 3f. 5inch at the bottom. The lintel is 5f. 10in. long, 1f. 1½in. in thickness and 11 inches in depth. This doorway is ([Added in pencil:] in the thickness of the wall) covered over-head with four stones laid horizontally across, the second rising 9 inches above the first, the third 6 inches above the second and the fourth 6 inches above the third, so that the doorway would be 21 inches higher on the inside than on the outside, were it not that the solid rock on which the wall is built rises in proportion, and it was to keep the doorway the same height through the whole thickness of the wall that lhe Cashellor was obliged to raise the stones (covering) the top One above (the other) in the manner described.

At this doorway the external part of the wall only remains perfect, measuring 4f. 5in. in thickness, and the other two divisions are nearly level with the area of the fort, bul immediately to the north and south of it, they are tolerably perfect.

In the N. West side of this ring, there is a passage leading from the inside into the thickness of the wall to the extent of 5f. 6inches measuring 2f. 9in. in width at the top, and 3f. 7in. from the bottom to the roof, where it is covered by large stones laid horizontally across. I should like lo resuscitate the spirits of Michen, Rigriu and Garbhan to ask them for what use this little chamber was built. Perhaps it was a bed? I would consider myself safer in it on the night of the "big storm" than in St. Kevin's Kitchen, unless indeed that I mighl dread being smothered by the spray (Cáitheadh) Fairge) of the Atlantic, which on that night passed over the whole island. Was this the Bed of King Aengus? No!

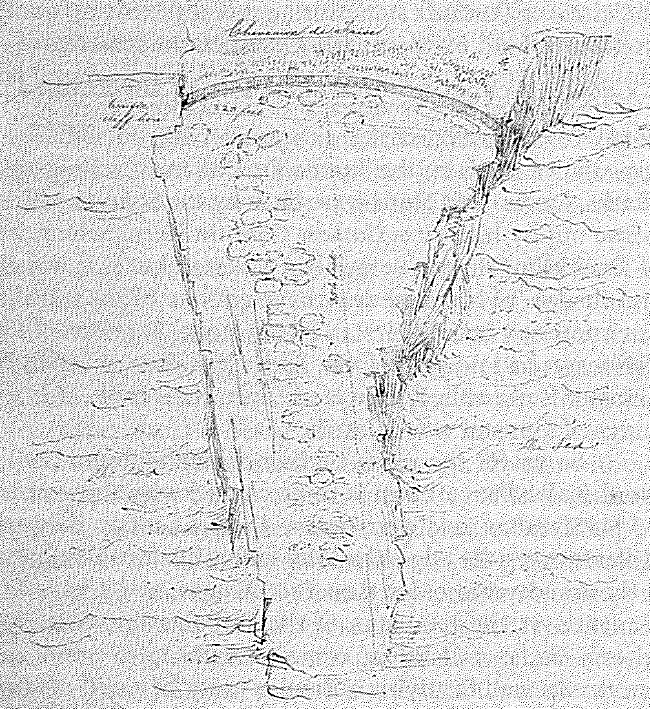

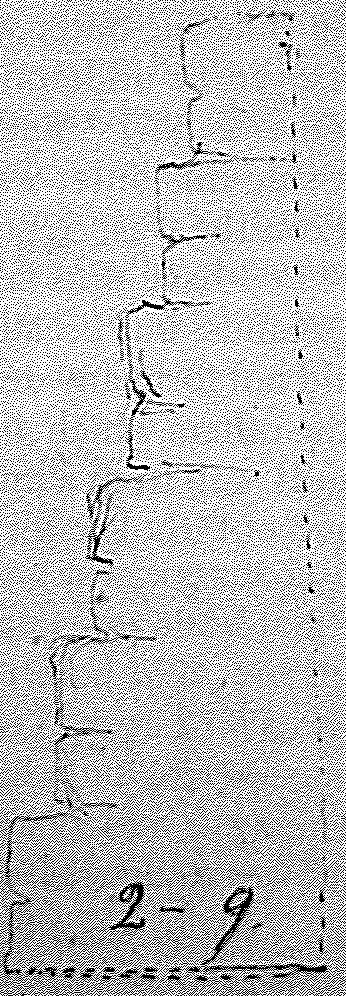

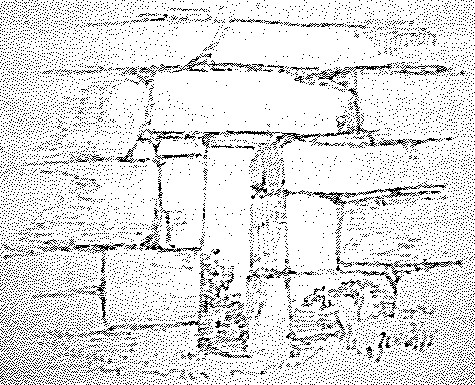

The following sketch will convey an idea of the masonry of this great wall.

Outside the internal Keep are the remains of a strong Cyclopean wall, which surrounds it at irregular dislances. Immediately to the west near the cliff it is within 28 feet of the wall of the keep; to the North and by west it is 32 feet from it, and to the N. West 42f. 6inches. To the north from the Keep this wall is in tolerable preservation, for here its original thickness and perhaps height remain. It is 6 feet thick and 12 feet high, and well faced inside and outside wilh stones of considerable size. It consists of two distinct walls one built up against the other, so that if the outer part were destroyed the inner part would stand firmly without it. A line drawn from this part of the wall to the doorway of the internal fort or keep measures 131 feet. In the N. East part of this external wall there is a doorway now much destroyed. It is 4ft 7inches. in width, and the wall is here 8ft. 2in. in thickness. A line drawn from this doorway to that of the internal fort or keep measures 235 feet. At the distance of a few feet to the east of this broken doorway this wall forms an angle from which a straight line drawn to the doorway of the keep measures 240 feet. From this angle the wall turns soulhwards towards the cliff, which is now very much destroyed. Its length from the angle above mentioned to the brink of the cliff is 176 feet.

Outside this second wall is placed a host of sharp stones slopewise, which to a mind as imaginative as that of Baron Swedenborg, would seem an army of Bolgians

who, (having been) placed here to guard the pagan fortress, were metamorphosed into tall stones by the Royal St. Endeus, whom (and whose satellites) they altempted to repulse as he was going to preach the truths of Chrislianity to the Toparch of Dun-Aengus. Here an army of stones present themselves; the army of the garrison (of Dun Aengus) in the various attitudes of fight, arrested in their progress and transformed into angry stones! Some in the proud majesty of defiance, some giving the charge, and some falling as if after receiving a death wound! To drop fables, some of these stones appear at a distance like soldiers making the onset, and (many of) them are so sharp that if one fell against them they would run him through. This army of slones would (appear to have been) intended by the Bolgae of Aran to answer the same purpose as the modern Cheveaux de Frise, Turnpike or Tourniquet, (now) generally used in making a retrenchment to stop cavalry; but these stones were never intended to keep off horses, as no horses could come near the place without "breaking their legs". They must have been therefore used for keeping off men, and very well adapted they are for this purpose, for a few men standing on the outer wall just described, could (by casting stones), kill hundreds of invaders while attempting to pass through this army of sharp stones.

This brings to my recollection an Observation of Martin's written in his account of the Island of St. Kilda p. 19, where he says:

There is a little old ruinous fort on the South part of the South East Bay, called the Down. It is evident from what has been already said that this place may be reckoned among the strongest forts {whether natural or artificial} in the World; Nature has provided the place with store of Ammunition for acting on the defensive; that is, a heap of loose stones in the top of the hill oterveaul, directly above the landing place; it is very easy to discharge volleys of this ammunition directly upon the place of landing, and that from a great height almost perpendicular; this I myself had occasion to demonstrate, having for my Diversion, put it in practice to the great satisfaction of the inhabitants to whom this defence never occurr'd hitherto. They are resolved to make use of this for the future, to keep off the Lowlanders, against whom of late they have conceived prejudices. A few hands may be capable of resisting some hundreds,

if the abovementioned weapons be but made use of.

This army of stones are (is) in some places 30 feet deep {in breadth} and extends all round (immediately outside) the second wall from cliff to cliff. They are (nearly) perfect on the west side, and also on the east, but on the North east many of them have been removed by the islanders to facilitate (the) passage to the sea.

Outside the second wall and between it and the Cheveaux de Frise there is another fragment of a wall, which seems never to have been carried around more than about the one tenth part of the ring. The part of it at present standing is 7f. 9in. in height and 6f. 0in. in thickness.

Outside the Cheveaux de Frise of stones there is another wall which encloses a great extent of ground, and runs from cliff lo cliff. A line drawn from the North (and by) west side of the second wall to this, passing thro' the Cheveaux de Frise, measures 129 feet, and a line drawn from the northern point of the same wall in a north west direction to an obtuse angle formed by this at the N-west point, measures 393 feet. This wall is here very much injured, but from what remains of it I have been able to ascertain that it was built exactly similar to the second wall already described, that is, formed

of two distinct divisions which would stand independently of each other. A line drawn from the broken doorway in the second wall already mentioned to the N. East point of this measures 434 feet. At this point I have been able to ascertain that the wall was 8feet. 0in. thick and well built, but the (original) height could not be inferred from any fragment of it now remaining. A line drawn from this point to the edge Of the cliff measures 586 feet, and a line drawn from the second wall at the edge of the cliff to the extremity of this (at the edge of the cliff also) measures 640 feet. At this side of the fort (outside this wall) the ground is low, but there is a remarkable elevation and unevenness of surface between it and the second wall and here the stone Cheveaux de Frise is very perfect. {See ground plan}

The pseudo-antiquary Ledwich stales positively that this great fortress was a monkish mandra or enclosure (for cattle!). To shew his (ignorance) barefaced effrontery, and disregard of (for) truth I shall here quote his words (as they stand in his own corrected copy) and shew how he attempted to blindfold his readers by concealing what he well knew to be the truth. He introduces the subject by giving Bede's description of a church built in England by an Irishman in the 7th century.

In 684 Cuthbert, an Irishman, and Bishop of Lindisfern, constructed an edifice of which Bede gives this(a)(a)

[NOTES BY JOHN O'DONOVAN]

(a) Vita Cuthberti p. 243.

(b) This exactly corresponds with St. Molash's Cashel on Inishmurry and with St. Brendan's on Inish Gluaire off the coast of Erris, and with St. Fechin's on Ard Oileán near Omey.

(c) It is to be regretted that Bede does not here describe the form and extent of these houses. In Lib. 3, c. 25, he tells us that the Scots never built any churches of stone but of split oak. Speaking of a church built by St. Finian at Lindisfern he writes: "Quain more Scotorum non de lapide sed de robore secto totam composuit, atque arundine texit. Eadbertus ablatâ arundine plumbi laminis eam totam, hoc est et tectum et ipsos quoque parietes ejus cooperire curavit. [JOD]

(d) The style here is very bad: what he intended to say is this: Though the numbers here recited are not to be depended upon, they being exaggerated by enthusiastic admirers of monachism, still they must evidently have been very great, and this &c.

(e) Ingens opus lapideum sine coemento tamen, quod ducentas vaccas in area contineret, supra altissimam maris crepidinem è vastae malis rupibus erectum. O'Flah: Ogygia p. 175. Mac Pherson's Crit: Diss: p. 294. {Dun Aengus would contain 1050 cows within its area. See ground-plan. JO'D}

description. The building was round, four or five perches wide between wall and wall. The wall on the outside, was the height of a man, on the inside higher, so made by sinking of an huge rock, which was done to prevent the thoughts from rambling, by restraining the sight. The wall was neither of squared stone nor (or) brick or cemented with mortar but of rough unpolished stone,(b) with turf dug up in the middle of the place and banked on both sides of the stone all round. Some of the stones were so big that four men could hardly lift one. Within the walls he constructed two houses(c) and a chapel together with a room for common uses. Within the walls was a large house (.i. An teach n-Aoidheadh) to receive strangers, and near it a fountain of water.

The paroxy[s]m of zeal for the monastic profession alternately possessed the eastern and western world. Egypt about the end of the fourth century boasted of seventy six thousand monks and twenty one thousand nuns. In this Island in the seventh century, the age we are speaking of, St. Nathalus and St. Maidoc separately ruled one hundred and fifty monks, and St. Manchen and St. Monenna as many nuns. Three hundred monks obeyed St. Tehan; eight hundred and seventy six St. Carthag; a thousand St. Goban; a thousand five hundred St. Laserian; three hundred St. Brendan; three thousand St. Finian; as many St. Congel and St. Gerald; so that Bishop might well say the secular and Regular clergy were almost as numerous as men of every other denomination. In the little isle of Bute were twelve churches or chapels, and thirty hermitages; and in Uist and the other Hebrides, religious phrenzy equally extended her reign. Hence the Irish acquired a fondness for, and a propensity to monachism, which remarkably distinguished them through every age. Though the number of monks and nuns now recited is by no means to be depended on, yet(d) it suggested to their presidents the necessity of stone enclosures or closes, these in the east were called Mandrae.

The word originally imported simply a sheepfold, and was applied to those monastic buildings, wherein the Archimandrite presided over his disciples, as the Shepherd superintended his flock in the fold. There are many of these Mandrae dispersed over this kingdom hitherto unnoticed; one remarkable is Dun Aengus. This is in the greater isle of Arran on the Coast of Galway, situated on a high cliff over the sea and is a circle(e) of monstrous stones, without cement and capable of containing 200 cows. The tradition relative to it is that Aengus, King of Cashel, about 490, granted this isle, called Arran naomh or Arran of the saints to St. Enna or Endeus to build ten Churches on.

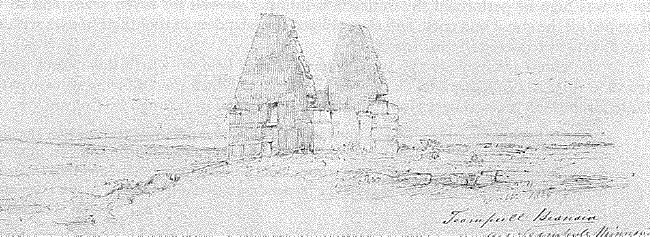

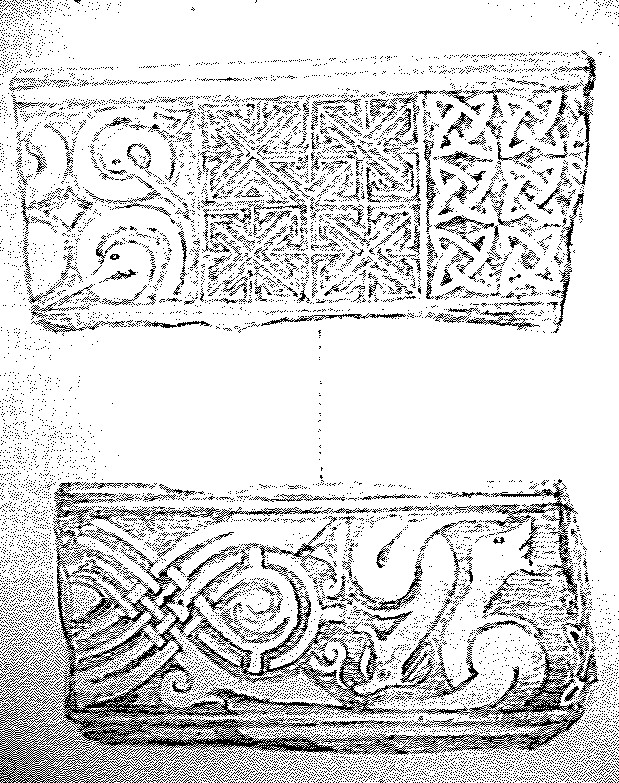

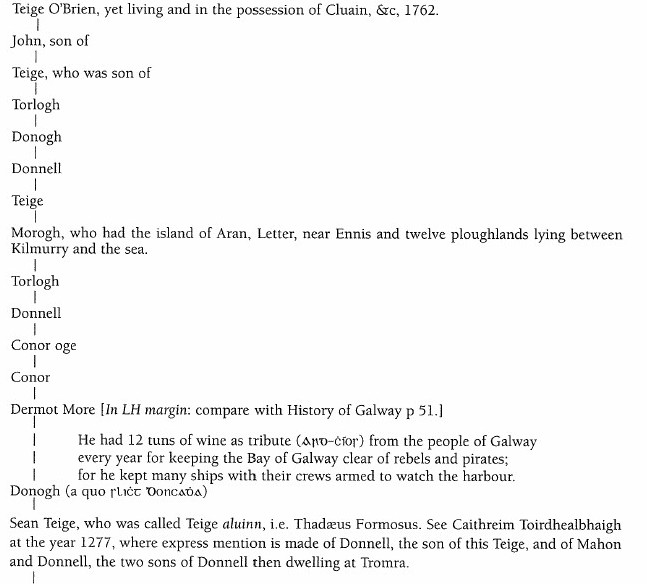

In order to make his readers believe that Dun Aengus corresponded with a Monkish Mandra he gives the foll annexed drawing of it, which is incorrect almost in every particular, being made up from his own imagination by W. Beauford, who, according to a MS. note found after Ledwich, was capable of any fabrication. In this sketch the wall is represented as perfect, {which it was not in Beauford's time} and (as raised to) about the height of a man to agree with Bedes's description of St. Cuthbert's Cashel at Lindisfern. A square wooden house of considerable height is shewn within the Dun and three smaller ones, but these did not exist in Beauford's time. A large tree is also shewn within the dun, and two crosses and a large tree in the foreground; but these never existed! The circle of the dun is represenled as perfect, which it was not these seven hundred years. Shame upon the Charlatan! So far Beauford imposed upon Ledwich; let us next see how far Ledwich imposed upon his readers (by distorting history): Reading the first note to St. Enna's life in Colgan {Acta SS. p. 710 Col 1} in which the Saint is called celeberrimus archimandrita, or most celebrated abbot, and hearing of the existence of Dun Aengus on the island of St. Enna,

he at once jumped to the conclusion that the Saint's wooden church and houses were within it; and to make this appear he distorts the written tradition in connexion with Dun-Aengus: he quotes O'Flaherty's Ogygia for its existence and extent, but suppresses what it says of its history, and he quotes Archdall to prove that it was called after Aengus, King of Cashel, who granted the island to St. Enna about the year 490. (But) O'Flaherty slates in positive terms (in the passage which is partly quoted by Ledwich), that it was the constant tradition in Aran that Dun Aengus was called after Aengus Mac Umore, (one of the Belgic chieftains), who flourished under Meave, queen of Connaught, a short time before the birth of Christ; and Archdall does not say a word about Dun Aengus at all! (nor about any tradition connected with it) and even if he had what weight could his authority have? But unfortunately for Ledwich's Charlatanism St. Enna's monastery is 5½ Irish miles from Dun Aengus, and Dun Aengus had never a church nor wooden house within it. So much for Ledwich's Mandra! {Compare wilh Inishmurry, Inish-Gluaire and Ard-Oilean, where the Monastic Cashels are described} The kind of houses which were within Dun Aengus I shall have occasion to describe presently in treating of Dubh Chathair. They are all now (so) destroyed

that I could not obtain the measurements of any one of them. See, however, Dun-Eogannacht, Dun-Conchobhair and Dubh-Chathair from which a tolerably correct idea may be formed of the original form, extent and characteristics of Dun Aengus, and of the kind of houses which stood within it.

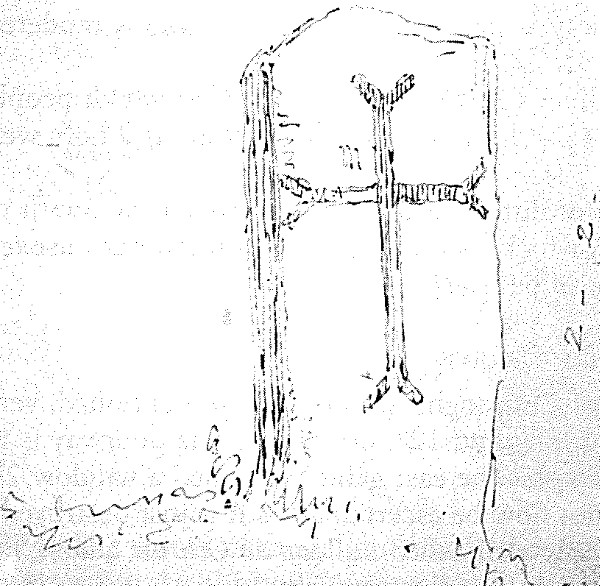

The only bronze antiquity remembered to have been found on this island, {with the exception of pins,} was found not many months ago in the interior of the wall of Dun Aengus, by boys who were rooting for rabbits. It was probably a fishing hook belonging to Aengus! It is 3¼ inches long and it (is) rivetted near the turn of the hook. Theannexed sketch is of the size of the original.

PAGAN ANTIQUITIES CONTINUED

II. DUN EOGANACHT

([On an unnumbered page in the hand of Eugene O'Curry:] Eoganacht Ninuis, i.e. Eoganacth na n-Arann, a district anciently in Corcomroe. See the Wanderings of Maeldinn, in Leabhar-na-h-Uidhre. EC.)

Situation. This fort is situaled in the Townland of Eoghanacht which forms the western portion of the island. It is built on a rock, which, (forming a cliff) on the Norlh side affords it great protection.

Name. This fort is not noticed by Roderic O'Flaherty nor any other writer who has treated of the Islands of Aran. Its original name is lost, and the present it takes from the townland in which it is situated. This townland has derived its name from a Munster tribe who settled in it at an early period; but we have no historical monument to shew the exact year or even century. The only notice to be found in Irish history about the Eoghanact of Aran appears in that part of the Book of Lecan called the Book of Munster in which it is distinctly stated that there were seven tribes in Ireland and one in Scotland called Eoghanachts, i.e. descendants of Eoghan, son of Olioll Olum, King of Munster in the 3rd century. These were the Eoganachts of Aine in the now County of Limerick, the Eoganachts of Loch Lein, at Killarney, of whom O'Donoghoe was the chief, the Eoganachts of Cashel of whom O'Callaghan was chieftain; the Eoganacts of Raithlenn; the Eoganacht of Glenn Amhnach in the County of Cork, of whom O'Keeffe was the Senior; the Eoganachts of Aran mor in the Bay of Galway, of whom nothing is recorded; the

Eoganachts of Ros-airgid, and the Eoganachts of Magh-Geirrgin, a (level) district in which the town of Fordun in Marr is situated. See Ogygia Part III, c. 67.

We have nothing, as far as I know, to fix the period at which the Eoganachts established themselves in this townland, but it is probable that it was some (time) after the establishment of Christianity for it appears from the life of St. Enna that on his arrival on the island, it was occupied by Pagans out of Corcomroe {in the now County of Clare} who were governed by a wicked leader of the name Corbanus. From this it will appear pretty certain that the Eoganachts had not yet arrived, and if conjecture were allowable, I would suggest that it is highly probable that they were sent by Aengus, King of Cashel, and head of the Eoganachts, to St. Enna to inhabit the island after the expulsion of the tribe of Corcomroe. See Life of St. Enna C. 15.

In an Inquisition taken in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, the Great island of Aran is stated to consist of three townlands, the one called Trian Muimhneach {the Momonian (ternal) division} the other Trian Connachtach {the Connacian third} and the third Trian Eoghanacht, {the Eugenian third.}

I do not believe that this Dun was ever built by the Eoghanachts of Aran, but by the same people who built Dun Aengus and Dun Conchobhair, though I have no doubt that they dwelt wilhin it down to a considerably late period.

This Dun is nearly circular, it being 91 feet from north to South and 90 from east to west. Like Dun Aengus its wall consists of three distinct divisions regularly faced with stones of considerable size, and which would stand firm independently of each other. On the South side the entire thickness of the wall is 16 feet, the innermost division being 4f. 0in., the central division 4 feet and the outermost 8 feet. This wall is in good preservation and is at present from 12 to 16 feet in height. The doorway, which is nearly destroyed is placed in the S.E. side. The original breadth was 3f. 4in. but its height or other characteristics can never be ascertained.

There are remains of (four) flights of stone steps leading to the top of this wall from the inside, one at the north, one at the east, the third at the south, and the fourth at the west side, but they are so injured as not to merit (minute) description. See the Dun of Eochaill, where similar steps occur from a description of which an accurate idea may be formed of the kind of steps which originally [led] to the tops of the walls of all these forts.

This Dun had never any outer works like those at Dun Aengus, but it is built of stones

much larger and its wall is several feet thicker. Near the broken doorway lhe stones are enormous (not monstrous!).

This fort commands a panoramic view of the "North shore" and the Twelve peaks of Connamara.

About half a mile to the west of this Dun there are two of those little houses which O'Flaherty calls Cloghans

They have Cloghans, a kind of buildings of stones layed one upon another, which are brought to a roof without any manner of mortar to cement them; some of which cabbins will hold 40 men on their floor; so ancient that no body knows how long agoe any of

them were made. Scarcity of wood and stone of fit stones, without peradventure, found out the first invention.

p. 75.

The more perfect of these Cloghans, is not of a conical shape like those on Inis Gluaire in Erris, bul of an oblong form. It is 14f. 3in. in length from east to west and 6f. 2in. in breadth from South to north. It is angular in the corners at the west side and rounded at the east side. (Every stone hangs above that immediately below so that the two sidewalls are so near each other at the top as that one stone extends from the one to the other.) The roof is (thus) covered (in) with ten long flags laid horizontally across at the height of 8 feet from the level of the floor.

There are two doorways on this Cloghan, one on the South side which is now stopped up and the other in the north side, which is opened so as that one can enter it, bul I could not without great trouble ascertain its original height. The lintel of this doorway is on the inside 4f. 8in. long, 9 inches deep and 1f. 0in. in thickness. The thickness at the doorway is 3f. 5in. The lintel which traverses this doorway at the top on the outside is 3ft. 10inch. [long], 8 inches deep and 1f. 4in. in thickness. On the outside this Cloghan is as irregular as a carn.

Immediately to the N.E. of this there is another Cloghaun having half its roof destroyed. It measures on the inside 18 feet in length, and 7ft. 5inch. in breadth. It was in (en)tered by two doorways, one in the north wall, the other

in the south one. The south [?recte north] door is 1f. 8inch wide and the South one 1f. 9in. one [sic], but the height could not be ascertained without going to great trouble in clearing away the stones.

These houses which, as I shall presently shew, are to be found in many other parts of the island, are not unlike the female Warrior's house on the Island of St. Kilda (and the Staller House on Borera Isle), which are described by Martin thus as follows in his interesting account of that island:

Upon the west side of this Isle there is a valley with a declination towards the Sea, having a rivulet running through the middle of it, on each side of which is an ascent of half a mile; all which piece of ground is called by the inhabitants, The Female Warrior's Glen; This Amazon is famous in their traditions: Her house or Dairy of Stone is yet extant; Some of the inhabitants dwell in it all Summer, though it be some hundred years old; the whole is built of Stone, without any wood, lime, earth or mortar to cement it, and is built in form of a circle pyramid-wise towards the top, having a vent in it, the Fire being always in the centre of the floor; the stones are long and thin, which supplies

the defect of wood: The body of this house contains not above nine persons sitting; there are three beds or low vaults that go off the side of the wall, a pillar betwixt each bed, which contains five men a piece; at the entry to one of these low vaults is a stone standing upon one end fixed; upon [which] they say she ordinarily laid her Helmet; there are two stones on the other side, upon which she is reported to have laid her sword.

p. 23.

And again

In the west end of this isle ({i.e. Borera}) is Stallir House, which is much larger than that of the Female Warrior in St. Kilda, but of the same model in all respects; it is all green without like a little Hill; the inhabitants have a tradition that it was built by one Stallir, who was a devout Hermit of St. Kilda; and had he travelled the Universe he could scarcely have found a more solitary place for a monastic life.

p. 43.

See Macauley's description which is much more minute.

About 220 yards N.W. of Dun Eoghanacht are traceable the foundations of an oblong house 20 feet by 13, and which had two doorways, one in the east wall and the other in the west. Close to the fort are the remains of similar buildings, 19 feet 7 inches long, and 13 feet from doorway to doorway. To the N.E. of the Dun are the foundations of three others of similar form and equal dimensions. These are the remains of the Cloghans described by O'Flaherty in 1684, (some of) which "would hold 40 men on their floor".

Immediately to the east of the Dun there is a small stone enclosure with three upright stones in its centre. It is called Kill Chomhla or Kill Chonan, and said to be the grave of a saint. Colgan mentions a church called Kilconnan near Teampull mór Enna on the other end (side) of the island.

PAGAN ANTIQUITIES CONTINUED

III. DUN EOCHLA

Name. The ancient name of this fort is also lost, and its present one is derived from the townland in which it is situated. Eochoill, is (certainly the ancient) name of this townland (but it) is called by mistake Leamchoill in the life of St. Enna written by Augustin Mac Raidin about (the year) 1390, for Leamhchoill is the name of the next land on the opposite shore of Garomna island, from which St. Enna is said to have set sail for Aran. It is probable however that this mistake was committed by Colgan in publishing Mac Raidin's text, and that both places were mentioned by the latter. "St. Enna set sail from Leóchoill and landed at Eochoill" would appear to have been the original text of Mac Raidin. The word Eochoill is not explained in any Irish Dictionary or other work worthy of attention, but it is evidently compounded of Eo and Coill. The meaning of the latter part of the compound is certainly 'wood' but the meaning of the former part Eo may be doubted; I have been these seven years under the impression lhat it is the Irish for Yew, but on turning to the authorities I cannot find a single example of its use. The word used in

the earliest MSS., for yew is Iubhar, which is explained in Cormac's Glossary as derived from eo, i.e. semper, and bárr top or foliage "quia frontis honores (.i. folia) semper virides sunt". On turning to Colgan I find that he understands the word eó as signifying the oak not the yew; thus in giving the derivation of Maigh eo {Mayo} he writes:

Monasterium Hibernis vulgo Mageo i.e. Campus quercûs vel juxta primum vocis etymon Magh-dá-eo i.e. campus duarum quercuum, latinis nunc Mageo, nunc Maio appellatum.

Acta SS. p. 604, Col. 2.

{Compare with Achadh dá eó, now Aghadoe in Kerry.} O'Flaherty speaking of the venerable trees of Ireland which were prostrated by a storm in the year 665, states that the one of them called Eó Mughna, which stood on the plain of Magh Ailbhe near the present Ballaghmoon in the County of Carlow, was an Oak tree, and the one called Eo Rossa was the yew.

Eo Rossa taxus fecit et ad ortum aestivum Drumbar Drumbar versus decidit.

Ogygia p. 313, Cap 60.

From this it would appear that eo was a generic word for tree, it being (at) one time applied to the Oak and at another to the yew; but it would appear to have been oftner applied to the oak {eó-óg! (a yoke!)}.

The next next question is, Was there ever a wood of yews or hoaks here? Could they strike root into the solid

rock? Let the Crannologist answer this question. There is however a tradition (on the island) that there was a "scrubby wood" of small hard oaks (and hazels) here some years ago in which the little boys and girls of the island were wont to gather nuts, and this (appears to me) probable, for on the north part of this townland near the sea there is a considerable depth of soil formed of decayed vegetables, in which small trees could strike root, but I don't agree with J. T. O'Flaherty or the author of the History of Galway in the opinion that this island was once overshadowed with wood; for in the first (place), there is little or no shelter, (from the Atlantic storms;) in the second, there is no depth of soil (in) any part of the island in which a large tree could be fed, and in the third place, the wintry (storms and) showers of spray which traverse this island from end to end, and from side to side, are calculated to destroy large trees. The only trees of any size at present on this island are in a little valley in Kilronan, but these present all the appearance of plants fed in an unfavourable soil, and withered by the sprayey breath of ocean storms.

The various tribes of the more humble plants however, flourish here (in health and beauty) in the rich soil formed by the decayed remains of their predecessors, and by (the) detritus of the limestone rocks with which

they are surrounded. One fact in connection with this subject (of trees) puzzles me very much: Why would not trees grow in Erris now as well as formerly? That they grew there in ancient times - and not many hundred years ago - is certain, in as much as (many) large trunks (and roots) of oak and ash are found there in the bogs and in the sand on the sea shore near Doonah Castle; and now Erris is so destitute of trees, that (when) a little girl, a native of that district came to the neighbourhood of Casllebar she fainted at the sight of a tree! mistaking it for a giant.

Can Captain Portlock or any of our modern men of Crannological science give any reason for this fact? Are the storms now more furious, or has the Salt water changed its qualities?

To return to the meaning of the word Eochoill. I think it means Oak-wood {eo-c sylv) and that a small wood of hard (dwarfish) oak grew here on the part which is now cultivated. Let others if they please, insist that the meaning is yew-wood because the English word yew or eugh as it was anciently written, (is nearer to it than the English word oak.) I have no other reason or authority to contradict such an opinion, but what I have above stated, and that there are no remains of yews there at present.

So far the name of the division of the island on which this fort stands. The Belgic name (of the fort) may have been Dun-Taman or Dun-Kima, but it is now totally forgotten to tradition, and ils history seems never to have been written, or if written long since destroyed.

Situation. This fort is situated on the highest point of the townland of Eochoill about 2 miles to the west of the village of Kilronan and adjoining the (Aran) Light house. It was a very important fortress, and the one which guarded (defended) the north side of the island. It commands a splendid view of the harbours on every side. To the west you have a view of the ocean; to the north-west of (the) Skerds, the rocks of which O'Flaherty tells such wild stories; to the north, at a considerable distance, of Mac Dara's Island and Cruach na Caoile, and of the 12 Stacks of Benna Beola, "robed in colours of the sky".

This fort is in a much better state of preservation than Dun Aengus, and merits particular description in consequence of the lights which it throws upon the original characteristics of the parts of Dun Aengus now destroyed. The ground falls a good deal on the north east side where the fort is very difficult of access in consequence of the unevenness of the surface and sharpness of the rocks. No Cheveaux de Frise are now observable outside this fort, and it is probable that none ever existed as the position was sufficiently fortified by the nature of the surface. It may be safely asserted that no horses could ever approach this fort, and men must have found difficult

to make a sudden assault upon it, in consequence of its commanding situation, and the difficully by which the rough fields of stone around it on every side could be traversed.

This Dun consists of two circles (or rings), the one surrounding the other at unequal distances. The internal keep is a strong Cyclopean wall of large stones (nearly of an oval form) without any kind of cement. The circle measures in length from north to South 91 feet and in breadth from East to West 75f. 6in. Like the other central wall of Dun Aengus it consists of three distinct walls built up against each other, and so well faced with large stones that they would stand independently of each other. On the North-east side in which the doorway was placed this wall is nearly destroyed, but on the South west and North-east (North-west) sides it is in good preservation. Its highest part is at the west side where it is exactly 16 feet high, and 10 feet thick. The next highest part is the east side where it is 13 feet high: here the two outer divisions of the wall are the same height and measure both together 8f. 8in. in thickness, but the innermost division is nearly destroyed down to the ground, but from a small fragment of it remaining its thickness is ascertained to be 2f. 7in. This

shews

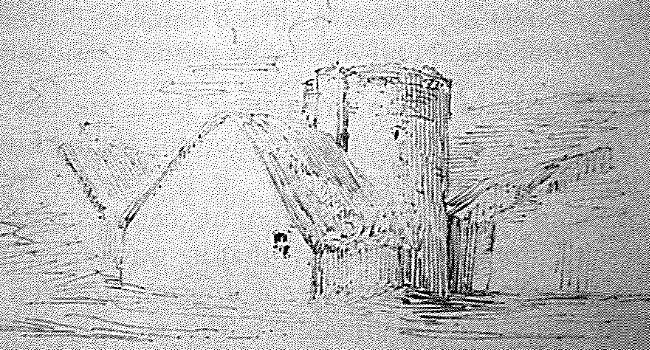

that lhe thickness of the three divisions was 11f. 3in., that is 1f. 6in. more than the thickness on the west side. On the west side the internal division is 7f. 9in. lower than the other two divisions, and it would appear that it was never higher though it is hard to conjecture why it was so low as it would be difficult to get up on the top of the wall from it. It is 2f. 6in. in thickness and 7 feet high above the floor of the fort. On the South and by west side a flight of stone steps leads to the internal division of the wall. At presera only 4 of them are visible, but there are at least 3 others covered by the stones (debris) fallen from the top. This flight is 4f. 1in. in breadth and runs within one step of the platform of the internal division of the wall. Ils inclination is 2f. 6in. from the perpendicular, thus:

The lowest step of these ([is] 1f. 2in. high and 0f. 7in. deep; the second) is 1f. 4in. high and 0f. 7in. in deep [sic]; the third 0f. 10in. high and 0f. 5in. deep; the fourth 1f. 1in. (high) and 5½ deep.